|

I've taken a little break from blogging about writing books in order to actually write books, a good trade as far as I'm concerned, but it's good to exercise the blog-muscle too. (Or really any muscles -- I also exercise somewhat less when I'm in the writing throes than when I'm in the prepping-for-writing-throes. My agent's point, and it's a good one, is, "Everyone can exercise. Not everyone can write." Fair enough.) Also we adopted a puppy from this very great shelter (should you find yourself in the greater Seattle area and craving a pet) called PAWS. Does everyone want to see a picture of said puppy, even though really she's a subject for another post? Of course you do. ANYWAY, the point of this post is not to look at puppy pictures nor to recommend a book but -- wait for it -- a book review. Never in my life have I recommended a book review. Never in my life has anyone recommended a book review to me. I can't recommend the book because I haven't read it yet. But the review, well, the review blew my mind. It's by Katie Roiphe for Slate on a new novel called The Blazing World by Siri Hustvedt. (Is it bad form to link an entire sentence? Whatever.)

I like Katie Roiphe though boy does she piss people off. Which is some of what I like about her. She started off pissing people off -- that is, she remains most famous for her first book, The Morning After, which argued (in 1993) that that statistic you hear that one in four female college students will be raped at school is a load of shit. She further argues that saying so does everyone a tremendous disservice and that saying to women who had sex when they wished they didn't that it wasn't their fault because they were drunk or felt bad basically keeps women second class citizens. What has always impressed me about this book is not the argument itself but that she wrote it in grad school while getting a PhD in English. Getting a PhD in English seems like it should have something to do with writing books, but it really doesn't, especially not this kind of not-about-literature book. Her writing this book during graduate school seems to me about as impressive as learning a foreign language during the World Series. I will also say it was timely and provocative, and too little is. She writes for Slate now, as well as other publications as well as other books, about a whole variety of topics, which itself has been criticized as selling out in some circles, that she was going to be this feminist academic powerhouse and instead is writing memoir and book reviews and thoughts on parenting and marriage (because really, what kind of feminist cares about self, books, parenting, or marriage? Jeez.) Anyway, this is a person who both can't win for losing and wins big time for losing, so even when I disagree with her -- she wrote an article once about how ridiculous parents are to get so worked up when their kids won't sleep and she just lets her toddler wander around her apartment all night -- I am challenged and intrigued. And challenged and intrigued are good. I will also point out the obvious which is two-fold: 1) much of the problem with her being edgy, provocative, critical, dismissive, judgmental, and prone to not giving a shit what other people think of her is that she's also female (as are her harshest critics). And 2) as you will recall from the start of this sentence, even though that's obvious, I feel the need to point it out. All of which is to say: when Katie Roiphe says stuff, you'd do well to give it some thought. And in this book review, she wonders whether, "in coming years, the most provocative work in feminism will be in novels....It may be that the challenges currently facing feminist thinkers, the subtleties of how sexism plays out...are better dealt with in fiction. Now that we no longer need to name or discover it--'Sexism exists!'--the flatfooted outrage...is too crude, too simplifying, too unchallenging, too predictable, and the novel's delicate touch may be precisely what is called for." (Bold ecstatically mine.) How great is that? Like many in my generation, I came to feminism early and without question. Then I read a thousand pounds of feminist theory in grad school from which I learned a lot of history but a very little praxis. My search therefore has been where to go from here. We've ferreted sexism out, but my generation has neither done nor said very much new about it. Roiphe's point is ferreting it out -- pointing to it, linking to it, blogging about it, lecturing about it, non-fictioning about it -- has proven insufficient. So perhaps fiction is the feminist way forward. Novels are how the message progresses and minds are changed and consciousness is raised and change occurs. Novels, AS ONCE THEY WERE, will be again where the new, smart, strong, provocative, important, political, timely things are being said on this front, said and heard and germinated. My own bias is for novels anyway. I am entirely a proponent of fiction being more true than non-fiction (after all, you can make it up). I have never had to be convinced that fiction matters and matters most of all, the case for which is a feminist one both historically and critically anyway. And still this seems revelatory to me. This makes me stand up and cheer! Who gets to carry the feminist mantle into the next wave? Novelists! To which I say: a) hell yeah and b) I'm so on it. Here is a list of reasons why books make the best gifts. (This is not self-serving. I don't mean my books. I mean books in general.)

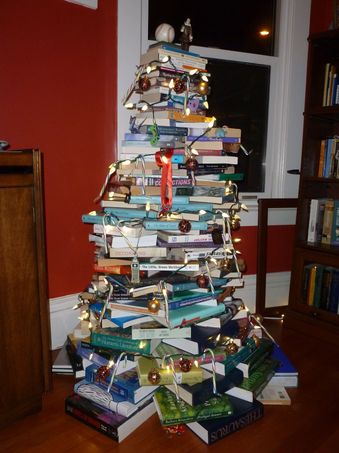

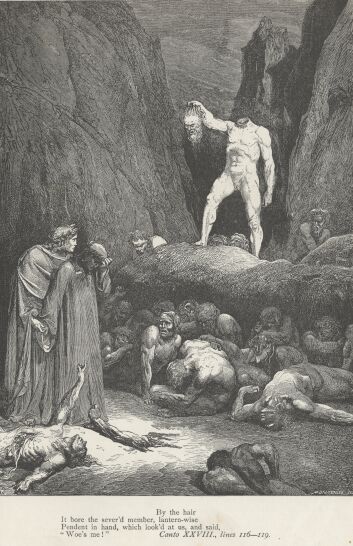

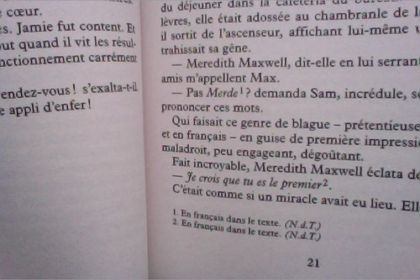

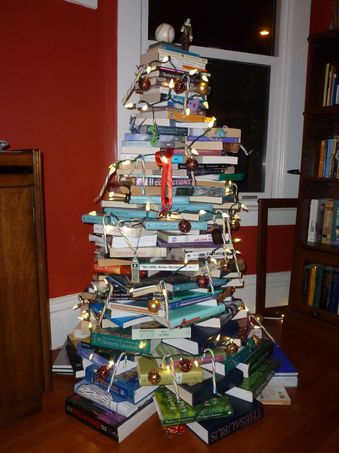

1) They are long lasting. It takes on the order of, say, ten or fifteen hours to read a book during which whole time your loved one is thinking in the back of her head how much you must love her for getting her such a lovely gift. Then, after she's finished, it will sit on her shelf in her living room or her bedroom and remind her of you. 2) They are personal, intimate even. When you get your loved one a book he really loves, he not only enjoys the book, he feels full of warm, fuzzy feelings that you picked it for him, that you knew him so well you knew how much he'd like it, that you think so highly of him you matched him up with this really great book. 3) Don't know how to pick the book that will result in #2 above? Books have a solution to that problem too. Walk into, say, the Gap and describe your loved one's personality and interests to the people working there, and they will not be able to pick out a sweater well suited to your loved one. Walk into a bookstore and do the same, and the people there absolutely will. Today, as part of Small Business Saturday, authors will be visiting local independent bookstores across the country to help you pick the perfect book for your loved one. (Find one near you with this handymap and/or google your favorite bookstore to see what they have going on today.) They aren't selling their own books, you understand; they are going to meet you, listen to you talk about your loved one, and offer the perfect book. (Authors tend to be very well and widely read, and this is our superpower. We are like Santa in this way.) That way you get to say to your loved one not only have I given you this great book but it was picked out personally for you by [insert name of fabulous author here]. 4) Even if -- perhaps, especially if -- your loved one owns some kind of e-reader, a book still makes the perfect gift. Now it's retro and nostalgic (sort of like the holidays themselves, especially for those of you still eating Chex Mix)(which should be everyone because Chex Mix is awesome). Now books stand out. Now your loved one will say, fondly, "Oh, I remember reading real books. How lovely." Personally, I like to go back and forth -- one ebook, one paper, one e, one paper. Your loved one will love having an actual object to unwrap and hold and smell and flip through and examine the cover of and then, finally, read and reread and look at and remember. 5) As regular readers will recall, books make great Christmas trees. Here's ours from last year. You can't do this with an ebook, my friends. I am totally fascinated/horrified by translation. It puzzles me completely. It is maybe one of the most American things about me that I speak only a little bit of one language besides my own -- and not well. I wish for other languages. I long for them. For the usual reasons -- they would make me a better citizen of the world; they would make me a better and more welcome traveler -- as well as the literary ones: I want to read Anna Karenina in Russian,Inferno in Italian, One Hundred Years of Solitude in Spanish. The world is such a small place and growing smaller and closer every day. Barriers tumble down. Technology brings us all closer together. So much of our experience of the world happens beyond language anyway. Blah blah blah. I don't buy it. Translation seems impossible to me. Miraculous, impressive as hell, and impossible. Let's talk about Dante's Inferno. It's a poem. In Italian, it rhymes. When you translate it, do you translate it literally word for word so that you get the exact plot and images and individual words Dante chose? Or do you translate it so that it rhymes at the sacrifice, sometimes, of much of the above? Before you answer, consider that much of Italian rhymes, much more than English does. So rhyming poetry sounds different and means differently to Italian ears than it does to English speaking ones. This kills me. "Um, I found a head. Does anyone know whose head this is?" "It's yours you idiot." "Really? Bummer. Man, I have a great body though, huh? Without my head, I look years younger. Anyone want it? Free head?" Another example is this: when Sam meets Meredith in Goodbye For Now, she says her friends call her Max, and he says, "Not Merde?" This is a joke. Because "merde" means "shit" in French. He calls her Merde throughout the rest of the novel because, to English-primary ears, Merde sounds like a cute term of endearment rather than a profanity meaning excrement. But what to do when you translate the book into French? My husband and I fantasized that they might change Meredith's name to Shitella or Poopina throughout in order to preserve the joke and its meaning/feeling/essence. (Right? Her name is Poopina, and the first time they meet he calls her Poop? Cute name if it doesn't mean, you know, "poop" to your ears. These are the things that amuse in my household). But instead, the very tasteful and talented French translator added a footnote the first time Sam calls her Merde which notes that it's in French in the original and otherwise has Sam call her Meredith. Which is perfect. Translation: The author is gross. I, the translator, am not gross. It is her. Not me. Cursing is a translation problem even in one's own language. I'm a curser. I curse. I curse at home. I curse in print. To my ears, it does not sound crude or dirty or especially edgy. I grew up with cursing. My father was a curser before me. He was a precurser. (You see how complicated language is?) I curse because I really can't see denying myself any of the language available to me. I want it all. But if you're offended by cursing, it sounds different to you, it means something different to you, than it does to me. Simply, you need a translation, just like someone who doesn't read English. What I mean by -- and not just literal meaning but everything that goes with it: sense, feeling, emotion, reference, character development, setting, local color -- "damn" or "shit" or whatever is simply not what you hear when you read those words. It's a disconnect. It's a translation problem. I don't intend to indicate that this character is crude or course or morally bankrupt or religiously doomed because to me cursing=normal. And in fact, in deference to those who would be offended, there's not a lot of cursing in my books. There's not a lot to begin with, and then I take a lot of it out in editing. Each time I come across a "bad word" (as if words could be bad), I consider whether someone out there might be offended and whether or not I could successfully change it to "crap" or some such. My first editor actually asked me to increase the cursing because she thought these were characters who would say "shit" rather than "crap." She was right. Ironically, I hate yelling. All yelling. I hate being yelled at. I hate being yelled near. I can't abide people who yell at one another, at their kids, even at tv screens. When people yell near me, I leave. Or cry. Or both. Cursing is not about anger. And I certainly never ever ever say it to or at anyone. The French translation of Goodbye For Now is also special because it's the only one I understand even a little bit. I don't read any of the other 25-plus languages into which it's been translated. But I read a little French. I understand the very lovely French edition mostly because I know what it says. But it's also a wonder to read my own words unfamiliarly, to make new to me something I not only made up but have read dozens of times. It's as close as I come to the experience of being a real reader of my own book. Kind of cool.

Sometime soon, I will write a blog post about Ruth Ozeki, who, ages before we met, changed my life in nearly all the important ways it has been changed. It's a pretty remarkable story, so stay tuned for that. Her new book, A Tale For The Time Being, has the greatest title ever and comes out in March, and really you'd think I'd have read an advanced copy by now because honestly I'm just not sure my patience can hold out much longer. Meanwhile, long after she changed my life in all those important ways, we met and became friends, and I'm very honored to be tagged by her in this bloggy-internet-y game of, well, tag. One author answers a list of questions on his/her blog, tagging at the end a handful of other authors who answer the same questions on their blogs, tagging a handful of authors in turn.

In her toss to me, Ruth mentioned that she hoped I'd talk about Goodbye For Now, even though the questions here are really about one's brand new or forthcoming or in progress work, and I shall. For several reasons. One, she asked me to. Two, my new, in progress work is just barely either one and not ready for discussion yet except by people married to me. Three, though I've answered these and similar sorts of questions on lots of other people's blogs, I haven't done so on my own blog. So here's theGoodbye For Now overview right where it belongs.

Right, so tagging. Remember freeze tag? Remember TV tag? Man I sucked at TV tag. Anyway... My friend and mentor, Jennie Shortridge, has her fifth (!) novel coming out this April, Love, Water, Memory. Great title, great book, great person all around. She blogs here. My new friend Tara Conklin's debut novel, The House Girl, releases next month. I've read it, and it's wonderful. She blogs here. I've been thinking about what we all experience the same way and what's different for everyone. I've been thinking about it because the two biggest, most demanding, most brian-occupying things in my life right now fall into the latter category: books and parenthood. I had been a mother for about an hour and a half -- on a 12-hour flight home from Korea which is itself another story -- before I realized children are all different and therefore all assumptions I had which began with phrasing such as, "When I'm a mother I will never..." or "Good parents always..." or "My children will never do that due to my superior parenting skills and general attitude as a human" were in fact a load of shit. Parenting seems like it's going to be a universal experience. It seems like one of those things that brings people together and unites us all. It seems like there are standards of good practice which will apply across the board. It isn't true. It isn't even almost true. In some ways, this is very freeing. I am now nearly judgement-free where parenting is concerned. Think Gatorade is a better choice than milk for your infant? Maybe. Prefer to dress you kid in a plastic trash bag than in clothes? Sure saves time. I say no to kids and guns and to Halloween costumes which equate children with sex. Otherwise, all bets are off. And books. You know why they say there's just no accounting for some people's taste? Because there's not. Lots of books are bad. Lots of books that are bad -- that I know are bad -- garner great reviews, sell millions of copies, and/or are beloved by otherwise seemingly reasonable people, thereby encouraging more bad books. And conversely, lots of books are good, and it seems like nobody knows it but me. In contrast to parenting, I am right about books, and everyone else is wrong. The books I like are good, and the books I don't are bad. I have seriously great taste in literature. This is true. Pissing into the wind. But true. In contrast, everyone experiences weather the same way. NYC darkens, floods, and we all feel either a) wet or b) helpless/empathetic/terrified/hopeful/appalled/alarmed/intrigued/ashamed which is something of a complicated emotion to be shared by everyone all at once. This is true of less dramatic weather too. As a writer, I find weather to be useful shorthand for all sorts of things. As a human, I find myself flirting daily for nine months a year with moving somewhere where it isn't raining. There is a reason why weather is the stuff of small talk. It's the thing we all share, not just the experience but the experience of the experience. I can't think of another thing about which this is so true.

When my husband and I moved into our current home seven years ago, we set up our four big bookshelves and then unpacked books onto them. When they got full, we did creative things like pile books on top of the bookshelves, and on the lips of the shelves in front of other books, and on and under chairs. Then we were out of bookshelf space, but we still had boxes and boxes of books. We couldn't buy more shelves because we had nowhere to put them (it's a small house). So into the attic they went. Last holiday season, we made a Christmas tree out of books in order to give more books someplace to be. We didn't use all our homeless books, but we used some. The tree is taller than I am. And it is still up. (For there remains nowhere else for the books to live.) This December, we might build a forest. We're that festive. (Or have that many books. You decide.) What? Your tree toppers aren't a baseball and a Shakespeare action figure? How come? The beauties of having books on hand are many, but the best is this: sometimes you need to consult a book for one reason or another, and instead of going to the library or the bookstore or the internet, you just go to your shelves and there it is. And not only is it there, but it smells like it did last you were reading it and so transports you right back to that time and place. Or some sand falls out because you last read it on the beach in Hawaii. Or a bookmark flutters out to remind you of the little shop where you bought it in London or the play you went to the night before you started it and whose ticket stub was then repurposed as a placeholder. And you've already made notes, written in the margins, underlined great passages, noticed smart connections. In fact, it's downright creepy the number of times I go to a book to look up something that has just this minute dawned on me only to realize that, nope, I've already written down that idea years ago right there in the margin. Once, I was reading about a book online which sounded interesting then on my way to the bathroom sometime later walked past my bookshelf where not only did I notice the book already there but found it already marked up, full of copious notes, and me with no memory at all of having read it. (Such useful memory-holes also mean I get to rematch tv shows as if for the first time. It's awesome.) And never mind I sometimes don't remember books I've read. I can often remember, years later, roughly where on a page and roughly where in a book a certain passage appears. So I can usually find a certain quote by flipping through because I remember that it was in the book's first third and on the top of a righthand page. And likely as not I've bracketed it and put exclamation points there from the first time through. My memory of books is tactile, olfactory, scavenged, and visual. Can't do any of that with an ebook my friend.

It is therefore very frustrating when I come up with a book I need to read/reread/consult/flip through, a book I know I own, and yet I can't find the damn thing. Is it in the tree? Can it be removed by jenga-ing it out and replacing it with a similarly-sized volume? (Often, I find myself in the book tree corner saying things to my husband like, "Let's go hiking this weekend. Find me an Inside Out Washington sized book.") Or is it still in a box in the attic? Or have I leant it out to someone? Or has it simply been lost in years of moving, packing and unpacking and repacking, shuffling books around and over and under and behind furniture, ready to reveal itself, perhaps, next time we move? ATTN EVERYONE: I need a new, larger house to buy and my copies of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and About A Boy. If you have borrowed either of the latter, please return -- no questions asked. If you are in possession of the former, we might ask a few questions -- you know, like have the place inspected -- but we're pretty easy. Built-in bookshelves a plus. Thank you. Here's something that's awesome: when random people you don't know write to you out of the blue to tell you they love a book you wrote. Twenty years ago if you read a book and wanted to tell the author so, I guess you went to the library, did some research (microfilm/fiche of articles written about that author that might mention a hometown by way of local color?), figured out where he/she probably lived, located a white pages from said hometown, and crossed your fingers the address wasn't unlisted. And hand wrote a letter. I have a borderline unhealthy amount of author-worship myself and did even as a child, and it's not just that I never did this; it never even occurred to me to do so. Nor anyone I know. My sister and her friend Sharon used to write love letters to Kirk Cameron pledging marriage. But no one I knew ever wrote to an author pledging so much as admiration. Now the research involved in locating an author is a .19 second google search. If you read your books as e-books, sometimes the link is actually embedded, so it doesn't even take that long (what will you do with your extra .19 seconds?). So lots and lots of people take a moment after finishing a book to look up the author. In fact, I wonder if it's most. And lots of those people take a few minutes or a little more to write an email or post on my FB wall or send me a tweet as to how much they like the book. This is, of course, gratifying in the extreme, and I am always very grateful. I knew I'd get some of those emails from my experience with book #1. What I didn't count on this time was how sad some of the letters would be, how downright heartbreaking. The book is about mourning, and a lot of people have written to me about their own losses, and those are very sad. Topically, I've gotten some emails from tech folks too and some from doctors, but the best/worst are the heartbreaking ones. I worked very, very, very hard to consider thoroughly and represent carefully mourning and loss from a variety of perspectives. In fact, though I didn't (and still don't really) know who these note-writers are, I thought of them while I was writing. I kept in mind always parents who lost kids to leukemia and brothers who lost brothers in car accidents and wives who lost husbands too early and what a shit cancer is. So I am grateful that this book gives some comfort/solace/recognition/support/diversion/remembrance to people who see themselves in it. But I am very, very sorry too. Meantime, if you've read the book and taken some time to write me a personal note about it, thank you. It means the world. P.S. That's not really my sister up there. Here's my actual sister (with my actual nephew). Kirk should be so lucky. P.P.S. Do you look up authors upon finishing their books? Do you usually drop them a note some way or other if you liked it? Do you ever write to authors of books you hate to tell them so?

The notion of vacation is a strange one when you work everyday but don't go to work any day and when work and not-work look so much alike. My husband, son, border collie, and I spent last week on Blakely Island with the wonderful writer Katherine Malmo and her family. On the one hand, it was vacation definitionally -- we were away from home. On the other hand, it was pretty home-like: same general topography if a much better view of it, same weather, same activities. In part, activities were the same of necessity. Small children will be entertained; they will leave the house; they will run about; otherwise, you will be sorry. Then they will nap during which you will try to accomplish something. Then they will need to be entertained out of the house whilst running again. In between, they'll need to eat. Blakely is not an island like, say, Oahu, with restaurants and such. It's the other kind. So another home-like activity on this vacation was the preperation of meals three times a day. Meantime, one of the very best things about writing as one's job is the fairly legitimate justification of reading books as work. Do I learn how to write novels by reading novels? For sure. Still? Even after all the novels I've read and the couple I've written? Hell yes. Can I continue to write novels without constantly reading them? No. No way. Do I take notes and add marginalia and look things up and write small essays reflecting on what I've read, what I've learned from it, and how I might implement those lessons myself? I do, always, but a) that is fun as far as I'm concerned, b) I've been doing it so long that it's part of reading for me, so c) that's not what makes it work. Reading is work insofar as it's part of my current job description. But it looks an awful lot like reading for pleasure. So on this vacation, while my kid was asleep, my husband and I sat out on the deck overlooking the sound, listening to ballgames on the radio, watching the sun set until about 11 o'clock every night, and reading books (and taking notes and writing about them -- well, I did that; my husband just read). It is indeed hard to overstate how amazing the view was and how different from the one off my own tiny deck. But is that enough to account for the difference in attitude? I'm not sure it is. Vacation reads are the best ones. And vacations just feel different from real life, even when you spend your days doing nearly the exact same things, even when you're blessed with a day job whose to-do list includes, "Read a new book." My vacation backyard. My actual backyard.

I have learned many (often horrifying) things in my three-plus years of being a parent. One is this: lots of children's literature sucks. This shouldn't have been surprising, but it was. When it had been thirty years or so since I'd read any children's books, I assumed that all children's literature was awesome because all of the children's literature I remembered was awesome. Which is why I remembered it. OF COURSE, children's literature, like all other kinds of literature, has some gems and lots of turds. I found this out by going to the library solo with my daughter. When we can, the three of us go together. That way, my husband reads to D while I pick out really good books to take home with us (or vice versa) (not books picking out really good versions of me to take home with them -- though that would be awesome -- but I read and my husband picks out books). But if you go just you and your three year old, she randomly picks things off the shelf that catch her eye and wants to read them then and there. Do you have a kid who will just sit quietly in the library and read to him- or (let's face it, probably) herself while you browse? Bless you. As most writers are, I was a huge and wide reader as a child. So pre-parenthood, I could name lots and lots and lots of awesome books I remembered reading as a kid. That turns out not to be because kids' books are universally awesome but because I repressed the ones that weren't. I know this because D picks out books that MAKE NO SENSE where NOTHING HAPPENS and characters are POINTLESS and the whole thing feels phoned in and depressing. And I mean, these are children, you know? They're innocents. They deserve better. My ONLY goal when I read to D is to teach her to love books and reading. How can I do that if the books suck? When we read aloud, my husband changes all the characters into accented foreigners: often British or Scottish, sometimes German, occasionally Irish or Minnesotan (not foreign but a good accent). I change firemen to fire fighters and policemen to police officers, and in books where EVERY animal or anthropomorphized character is "he," I change half the dinosaurs or sheep or pigs or cars or whatever to "she"s easily enough. We also don't read about Barbie, guns, or thinly veiled moralistic crap. Because D is adopted, I sometimes have to edit books that assume every single child on earth is parented by two married heterosexual people who had sex, became pregnant, and gave birth. This is what I was wary about going in. But it turns out there's shelf after shelf of terrible books out there just as necessary to avoid -- offensive not because they're sexist or racist or homophobic but because they are just SO bad. Narrative, people. Even children need narrative. Here are some new-since-I-was-three books we've found to love. What other newish and fabulous children books do you know? P.S. This is also, once again, why we need small bookstores and librarians: for help culling. And good writers and illustrators and artists and editors and book-makers: for making the world a better place.

I was in tenth grade the first time I read The Great Gatsby. In many ways, it was my first love. I'd been a big reader since, well, I learned to read. I had favorite books and literary obsessions. I made my parents read me the same books over and over and over again as a child. I was not a new book lover. But Gatsby was different. I was in love with it. I carried it around with me all the time, read passages over and over again during algebra and physics and other classes which, frustratingly, persisted in not being English class. I thought about the characters all the time as if they were my friends. I journaled about them. I talked about them to everyone I knew. I was so obsessed that, at my ten year high school reunion, almost everyone said something to me about the book, convinced, apparently, that that kind of love could not possibly have waned in the intervening years. When I told them I was in graduate school studying not American Lit but Shakespeare, many of my high school compatriots refused to believe me. They couldn't imagine the fifteen-year-old I was ever getting over that book. That's how in love I was. I have not seen the Robert Redford film. I couldn't imagine that it would live up to the thing in my mind, and I wanted to keep the thing in my mind, not supplant it with something else. I didn't see it when Seattle Rep did it live a few years ago. I have concerns about staging novels, but let's leave that for another post. But I will see the Baz Luhrmann. In fact, I almost can't wait until Christmas to do so. 1) I will see anything Baz Luhrmann does. Anything. 2) Look at it! It's gorgeous and so different. I know a lot of people -- like, all of them -- prefer movies to stay very close to the book, but I don't really see the point of that. In the same way that novels are not plays, books are not movies and vice versa. They are different mediums, good at and for different things, with different strengths and weaknesses. We already have The Great Gatsby in book form. What Baz Luhrmann is giving us is something new and different, adding to what's already there, to what we've already learned from the book, giving us more. Who doesn't want more? The book cannot be reproduced on film, so why try? Its strength is being something else instead, a different Gatsby riff. Show me who thinks this book and these characters are too small to be yet more. But 3) is best of all. Baz Luhrmann's films have a look about them. Baz Luhrmann's films sometimes star Leonardo DiCaprio. This one preserves that look and that star. And that means we cannot help but get a story wherein Romeo grows up to be Jay Gatsby. And he does! Of course he does! Impetuous, obsessed, lovelorn Romeo who moons about, whose whole world must revolve around love, who must, but must, give up everything for it OF COURSE grows up to be Jay Gatsby, still lovelorn and obsessed, still revolving his whole world around love but without seeming to do so, replacing the impetuousness with a more careful, more measured, more determined approach, more outwardly successful, still that heartsick, lovesick little boy inside. Both are undone by love, both victim to circumstances they have a hand at perpetuating but did not kick off and cannot possibly control, both are more sinned against than sinning (esp. in the Baz version where Romeo does not in fact kill Paris), neither can choose anything but love. Gatsby has all this experience, learning, worldliness, power, ambition, perspective, connections, and money that Romeo does not, a much much wider world, and he falls into exactly the same trap. It is so awesome. I could not love it more. And what percentage of high schoolers will read both of these texts and see both of these films? Um, like 95%? How great is it to be fifteen in the Age of Baz? So great! |

About The AuthorLaurie Frankel writes novels (reads novels, teaches other people to write novels, raises a small person who reads and would like someday to write novels) in Seattle, Washington where she lives on a nearly vertical hill from which she can watch three different bridges while she's staring out her windows between words. She's originally from Maryland and makes good soup. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed