|

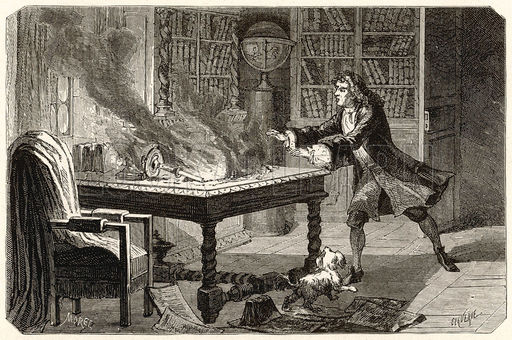

Here is an article from Slate last week on the first book ever to be written on a word processor. In 1968. The book's author, Len Deighton, explains, "Having been trained as an illustrator I saw no reason to work from start to finish. I reasoned that a painting is not started in the top left hand corner and finished in the bottom right corner: why should a book be put together in a straight line?" Which is a good argument. I'm not sure I'd have had the bravery/foresight/cash involved in knocking out a window of my home in order for a crane to install a 200-pound, $10,000 (1968 dollars, at that) typewriter in my home office, but the idea of processing words strikes me as remarkable even if you'd never heard of it before. IBM evidently never considered that these machines would be used by individuals. I get that these things were huge and expensive, but processing words has always, always struck me as the ultimate killer app. It's not that I can't imagine writing a book longhand or on a typewriter -- I can, and I imagine it was torture. As both a reader and a writer I came of age in a time of flexible, malleable, negotiable text. Messing with text feels like my birthright. It's as hard for me to imagine writing novels without a computer as it was for IBM to imagine me writing them with one, but I'm pretty sure I'd have chosen a different career. I thought a lot a lot a lot a lot about writing and technology for and of and as Goodbye For Now. Technotext is my text. But processing words, well that's just something I take for granted. I also like the note about how afraid he was of losing work to power outages. I am an anal backer-upper, so I totally get it, but anything electronic seems less worrisome than the alternative. I have long wondered how writers ever used to leave home in the days of hardcopy. What if your house caught on fire? Or the roof fell in? I have always had this backup plan: I would leave my hardcopy in the refrigerator. I mean dropbox is pretty awesome, but as a fallback, I'm not really doing anything with the meat drawer anyway. "Why oh why must I live in a time before cloud storage? Perhaps I am being karmically punished for caring more about my desk than my cute little dog."

It's easy to reflect philosophically on the election when you win. Sweep in fact. And it's nice to be able to listen to the news again. Last I heard, estimates were that this election cost six billion dollars. Six billion. Dollars. That's a lot of really good schools. Especially since very nearly everyone already knew who they were voting for before anyone had spent a penny. And especially since in most states it didn't matter anyway. What I've been thinking is that the technology inGoodbye For Now could have saved everyone a lot of time and money. The idea behind RePose is that it reads your emails and tweets and FB posts and such and figures out 1) who you should be dating and 2) the sorts of things you say and how you say them. It could also, far more easily I expect, figure out who you're going to vote for. Even better, it can figure out who you should be voting for. You may be undecided, but the software knows. Think of the money we could save. Think of the time and effort and energy. Obama must be exhausted. The man had to run for president while also being the leader of the free (and not so free) world. This is like pitching game seven of the World Series during halftime of the Superbowl you're quarterbacking. It defies belief. And much respect to Nate Silver, but I wonder what the miracle is here. That he was right? Or that the answer was knowable? Much has been discussed (in, say, census conversations) about whether actually asking everyone is the best way to vote/count/decide. If we already know, why/how do we ask? There are answers to that question, but they're not easy and they're not quite being widely discussed and they're not bipartisan, which makes them even harder.

Washington state is entirely vote-by-mail now, so in fact I voted a month before election day. I missed going to the polls because there is great camaraderie in standing in line for several hours with one's neighbors attempting to do something civic. My neighborhood is very African-American which made waiting to vote for Obama that much more stirring. I also remember voting with my mom when I was very little, her bringing me behind the curtain with her and letting me pull the lever -- that's stuck with me, and it would be nice for D to have that experience, that memory, and that civic understanding. Would it be as nice as it is not to have to stand in the rain for three hours waiting to vote? No. As nice as it is not to have to miss a day of work to vote? No. As nice as it is not to have to find daycare in order to vote? No. As nice as it is to be able to vote even if you can't get to the polls? No. So I'm with my once and future president on this one: we have to fix that. You see? This is what I'm talking about. Freddie Mercury died in 1991. Then he was in the Olympics Closing Ceremony this week. Depending on which account you read, this is presented variously from, "A video played," or "The segment started with old footage," to "Freddie Mercury's hologram 'duets' with Jessie J." Some people expressed relief Mercury didn't go the Tupac hologram route (which, regular readers will recall, wasn't really a hologram either). Others offered seemingly unquestioningly and unproblematically that Mercury fronted for his band Queen at the Olympics this week and led the crowd in song. Here, so long as Youtube doesn't take it down, is the video: I have questions. And, as good luck would have it, answers.

Q: What is the difference between this (or Tupac) and going to a movie? A: Audience participation. He called; they responded. Q: Okay then, what's the difference between this (or Tupac) and a singalong screening of The Sound of Music or The Rocky Horror Picture Show? A: In those movies, actors are playing parts. Here, Freddie is really Freddie. Q: So it's a film but of something real. Like during Shark Week? A: No because it's live. Q: No it isn't. Freddie's dead. A: Yes, but the audience is both alive and live. Living, sure, but more importantly present. Witnessing the event, live. Participating in it. Q: So, like a play? A: No, because in that case we have actors playing roles again. And also, probably, those actors are alive. Q: Okay, then let me ask this question: what, practically speaking, is the difference between an alive-Freddie Mercury performing at the Olympics and a dead-Freddie Mercury performing at the Olympics? A: You see a projection rather than a person. Q: Not really. Either way, aren't you watching him on the jumbotron? A: Yes, but you see a little tiny mini him down front, depending on how good your seats are. Q: Yeah, but you still see that little tiny mini him down front. It's just not really him. You'd have to know to know though. A: Hmm. Yeah, hmm. My question is less: isn't Freddie Mercury just archive footage at that point? And more: isn't Freddie Mercury just as real as alive at that point? Why do we need to be present/alive to exist, perform, and even interact with the living? I hope that doesn't sound bleak for I mean it exuberantly. My point is simply this: so very much of us does exist in electronic archive, far far more of us than of poor pre-tech-boom, pre-social-media Freddie. The difference between actual us and that archive is, I suspect, stranger and weaker than we imagine. This appeared late last week in my Twitter feed from HuffPost Books: QOTD: "If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking." --Haruki Murakami I a) love this and b) agree with it, and c) the next book, whenever I find time to write it, comes at least in part from a similar sentiment. The whole online echo chamber theory, well, it echoes for me. And it's scary. The argument is that as we get more and more of our news and ideas and philosophies and opinions and information and life approaches and narratives -- stories -- from Facebook and Twitter and other social media sites where we choose our friends and choose who to follow, the range of said ideas and stories gets narrower and narrower. We are friends with people who think like we do. They are friends with people who think like they/we do. We and they are all passing back and forth the same tidbits of information, liking and retweeting and sharing the same articles and notes and opinions and stories. Plus every time we say anything, everyone we know "likes" it and tells us how lovely and clever we are, not just because they're friends but because they actually agree. Not enough new ideas can muscle in through all that familiarity. Maybe they should call it the Narcissus Chamber. Which one of these kids looks most pleased with their own opinions and ideas? This versus, say, you used to read the newspaper that was your town or city's paper. I grew up between Baltimore and DC and so read the Baltimore Sun and the Washington Post. They got delivered to my door. In theory, the news they delivered was broad, unbiased, wide-reaching, multi-opinioned, and multi-perspectived. It was also, importantly, researched, vetted, double-checked, edited, proofread, and held to standards of truth. This is not, of course, true of my Facebook and Twitter feeds.

Social media and the internet generally are sold to us as great levelers of playing fields and democratizers of ideas and access. Once, you had to own a newspaper to get your voice and ideas heard. Now, all you need is access to a computer and an internet connection. As receivers of information though, in a lot of ways, we were doing better before. I hear more voices now, but they're all saying the same thing. You see why that's dangerous and problematic. And disappointing given the freedom and possibilities presented by the web. And insidious given our impression that it's the opposite of what it in fact is. And yet...last week, when President Obama came out and said he did indeed think same-sex marriage ought to be legal, my Twitter feed did a little dance, my Facebook had a party, the links my people passed on were all laudatory and celebratory and smart from a pro civil rights, pro gay marriage perspective. That's all I wanted to read, and that's all that came across my radar. Was Fox News as thrilled as my social media peeps? Was the Republican Party? I don't know. Because their opinions never crossed my computer screen. My Facebook friends are not anti-gay. My Twitter feed is liberal and loving. It was awesome. So the question you have to ask yourself is this: is it important for me to seek out dissenting opinions? Important for my education or for being a whole person in the world? A responsible decision maker? Haven't I something to learn from the fifty percent of people in this country who seem to disagree with me about all sorts of political issues? Given that I believe that if only the gay-marriage haters would listen to something other than hate-spewing media, they'd realize the error of their ways, shouldn't I also try to break out of my online echo chamber? Or is it permissible for me and my lower blood pressure to bubble and cocoon and ignore the haters? There's enough broken, enough hate, enough that doesn't go my way in politics, enough that makes me crazy, don't my Twitter feed and I deserve to high five then go out for margaritas and celebrate the ones we win? Maybe I will repost this after the book is out so that the overlaps here will blow your mind as much as they blow mine (i.e. after you have -- I hope I hope -- read the book), but this just happened, so now seems a good time to write about it. As you maybe heard, last week at the Coachella music festival, rapper Tupac Shakur made a surprise onstage appearance and gave a stirring, provocative performance. This was especially stunning since he was shot to death fifteen years ago. The ways in which this blows my mind are numerous. For starters, it wasn't, as you'd at first assume, archived footage -- that is, the audience was not just watching a cleverly projected film of a previous performance. Digital Domain, the company responsible for the image, promises, "This is not found footage. This is not archival footage. This is an illusion." Note the boast here: it's not real; it's an illusion. It seems more and more like what impresses us as a society is not what's real but what isn't real. The projection technology, meanwhile, the technology that makes this look so real and so believable, is decidedly low tech, shockingly low tech in fact. The Tupac appearance was quickly dubbed a hologram which just as quickly caused a zillion people to post online about how in fact it was 2-D whereas a hologram is in fact 3-D. This turns out to be smoke and mirrors, well, mostly mirrors actually. It's projected on mylar so one can both see it and seethrough it so that Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg can appear live and rap with Tupac, and you see all of them. I was thinking of Disney's Mary Poppins (1964) where Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke interact with animated animals. I was off. By a hundred years. In 1862, this same essential technology was used to dramatize a Dickens novella.Charles Dickens. 1862. Now they're talking about a tour. My question is this: is that a technological miracle, a resurrection, the chance for a whole new generation of fans to see a performer there was seemingly no chance they ever would? Or is it going to the movies? To summarize: 1) This technology: so unfathomably impressive and advanced, it seems the stuff of science fiction 2) This technology: so old, it was first used by the Victorians 3) This technology: so mundane, it's essentially a movie Charles Dickens: Dead. But real. Discuss.

|

About The AuthorLaurie Frankel writes novels (reads novels, teaches other people to write novels, raises a small person who reads and would like someday to write novels) in Seattle, Washington where she lives on a nearly vertical hill from which she can watch three different bridges while she's staring out her windows between words. She's originally from Maryland and makes good soup. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed