|

I love nice hotels. I also like slightly less nice hotels as long as I get to stay for more than one night. The miracle of even crummy, cheap, roadside motel type hotels is you leave for a few hours during the day, and when you come back, it's all clean and nice and new again, and you get to start over. There's something very perfect about that. Plus it's a pretty good metaphor. More often than you'd think, I set scenes in hotels. My first book opens in the Waldorf=Astoria (equal sign theirs) where I just went for the first time on a research expedition for novel number three which also opened there but doesn't anymore for reasons not clear to me until I set foot in the place. Also fodder for another day. Outside, there was this sign: which probably wasn't actually a directive from the universe to me but certainly felt like it. It's a gorgeous old hotel. Then there's this gorgeous new(er) hotel which I also visited for book research: the Ritz-Carlton New York, Battery Park (whose hyphen, let's admit, is a little passé). A scene I was writing hinged on the view from a suite in the hotel, so I needed to see a suite in the hotel and look out its windows. It was pouring rain in NYC, and I was wandering around in only a raincoat and hat because I am a Seattlite now apparently, and so a forecast of rain no longer suggests to me that I should bring an umbrella. Thus I showed up in the lovely empty lobby of this very posh hotel, soaked and dripping and bedraggled and asking politely to see and photograph a $1500 a night hotel room. The concierge was quite, quite skeptical. I explained as to how I was writing this book and really it would take only a minute and I promised not to even drip on anything. And he paused and looked askance and went and whispered with someone else and looked tempted to call security and looked tempted to throw me out and looked somewhere between alarmed and appalled at my very existence and said, down his nose, "I don't suppose you have a card or anything." I do. I fished around in my wallet and produced it for him. And a switch flipped. Suddenly, he was terribly solicitous and all smiles, very eager to help, very kind, delighted to take me up and let me into a room that was maybe one hundred times lovelier even than it had been in my imagination. Generally they require a permit for photos he said but I should feel free to just go ahead and take as many as I pleased. You understand I ordered these cards online. And you could too. They aren't certified by the Library of Congress or anything. This is the sort of reception one hopes will greet the revelation that one is writing a book. And it never, ever happens. So I was gratified. And as an aside, if you've the means, the suites at the Ritz-Carlton seem entirely worth $1500 dollars a night in my opinion. And they do keep out the riffraff. "This telescope is provided for your enjoyment while a guest at this hotel. Should you wish to take it home with you, a $1,000 dollar surcharge will be added to your account." (I am just kidding. Probably if you pay $1,500 dollars a night for a hotel room, they throw the telescope in for free. Like how it's implied in your $99 a night hotel room that you may take your leftover shampoo if you wish.) In fact though, the case I want to plead is for the opposite kind of hotel room. I did a couple book events recently at a wonderful bookstore called Auntie's in Spokane, Washington. Spokane is so far east of Seattle it's very nearly in Idaho, and its hotels were all booked so I stayed a bit out of town, even easter, maybe only eight or ten feet from the border in a Comfort Inn which cost not even 100 dollars a night and was exactly what you are imaging. And it was perfect. In New York City, it doesn't matter how nice your hotel room is -- there's too much else good on offer to spend very much time there. In between Spokane and the Idaho border? I think there was a Subway down the street where I could have hung out, but otherwise nothing. So I sat in the room and wrote. All day. The room was spacious and neat and comfortable with a nice big window (overlooking the parking lot), climate control free and at my fingertips, a large desk and chair, free wifi, a TV in case I needed a break, a bed in case I needed a nap. Just downstairs was a hot tub, a workout room, a pool so I could have a little (very little, but still) swim. When I finished availing myself of these, I returned to a newly clean room, newly made bed, sparkling bathroom. Breakfast was plentiful and included and did not even require my putting on shoes (I did. But I didn't have to.) plus hot coffee and tea all day long plus soup in the late afternoon plus cookies in the evening. It was quiet and interruption/distraction/temptation free. For $99 a night, you could do a lot worse in the way of a writing retreat. There's much ado these days about romantic writing retreats -- on the train, say -- and though I get the romance, a train is going to be much more cramped and loud and public and distracting and with way grosser bathrooms and a much flimsier desk than one's very own hotel room. For me the only wrinkle is that Practically-Idaho is a solid five hours from Seattle, and though the ride there had been 60 degrees and sunny and so I'd put the top down on the convertible, when I left to go home, it was 35 degrees, and I could not get the top back up. And having packed for the former -- and for being in the car besides -- I'd not even brought a jacket. FYI: car heat does not stay in your car at highway speed if you don't have a roof. Strange but true. It was a long, cold drive home. But a good writer's retreat. A trade I am always willing to make.

As I have discussed -- here? elsewhere? mostly in my own brain? -- the beginning stages of novel-writing look a lot like wandering around the house aimlessly. Followed by writing. Followed by revision. Followed, only then, by obsessing about language. Novel-writing is long -- for me, in the early stages, language-matters are indulgences that interfere with the work that must be done: research, writing, revision, and wandering around the house. But that obsession with language is hard to let go of. During early-stage novel writing, it comes out in other ways. Example from some crackers I was eating this weekend: "Natural Flavor with other natural flavor." Natural flavor with other natural flavor? Look, I hate to be a graduate student about this, but: a) Can I get an S? Natural flavorS with other natural flavorS. b) Or articles? A natural flavor with another natural flavor might also work. c) What does this even mean? Are we talking about flavor or ingredients? Flavor means taste. Is their point that these crackers taste like two things? Crackers and sweet onions? Sweet potatoes (their main ingredient which is why I bought them. I am a sucker for sweet potatoes) and rice? Salt and crunchy? Bananas and bologna? Flavor and flavor? d) Or do they mean ingredients? Because flavor does not mean ingredients. But that does seem to be what's implied here. I chose these, in fact, because their ingredient list was short, recognizable, and non-chemical. These crackers contained actual foods on their ingredient list, foods such as sweet potatoes and rice. But then you'd think the copy might read: Sweet potatoes with rice. Instead of natural flavor with other natural flavor. e) Flavor means taste. All flavors are natural. Their cause might well be artificial, but their taste on the tongue is natural. And natural. f) There are only two reasons makers of crackers put copy on their boxes: to make me buy them or to make sure I don't sue them for having done so. I honestly can't imagine which this is. And then check this out: This sign is in the women's locker room where my kid takes swim lessons. I can only assume this is vandalism, a joke, but if so it's awfully well done -- I couldn't see any scratched out or scraped off letters. It is, in any case, someone's intention, be it the makers and hangers of the sign or someone with a pretty good sense of humor. So I ask you:

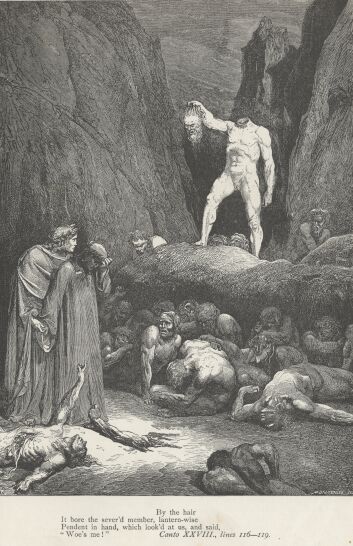

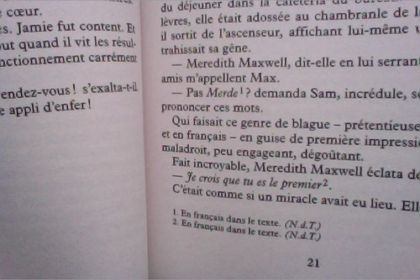

a) Is the final word here meant to be gender? Because at the very least they probably mean sex. Unless b) they mean gender in which case bravo and more power to 'em though I'm not sure that requires signage at that point. Maybe this is too long: "Children six years [of??] age and older must use the locker room which best aligns with their gender performance always acknowledging that that performance is culturally imposed and interpreted, subject to change, and may lie outside the two (falsely dichotomous) locker room options herein presented." c) Or maybe it's literal where end=genitalia. Which I love. d) Or maybe it bespeaks everyone's eventual demise. We don't want to think about it in very young children, but by six, you're old enough to consider that someday we must all shuffle off this mortal coil. Another too long sign: "Those whose off-shuffling will be in a car, a body of water, a hospital room, a mountain slope, or a dog park must use the women's locker room. Those for whom it will be a bedroom or other room in a private home, a yoga studio, a glacier crevasse, a boat, a ballpark, or a movie theater must use the men's locker room. We know you don't know, but guess." I am totally fascinated/horrified by translation. It puzzles me completely. It is maybe one of the most American things about me that I speak only a little bit of one language besides my own -- and not well. I wish for other languages. I long for them. For the usual reasons -- they would make me a better citizen of the world; they would make me a better and more welcome traveler -- as well as the literary ones: I want to read Anna Karenina in Russian,Inferno in Italian, One Hundred Years of Solitude in Spanish. The world is such a small place and growing smaller and closer every day. Barriers tumble down. Technology brings us all closer together. So much of our experience of the world happens beyond language anyway. Blah blah blah. I don't buy it. Translation seems impossible to me. Miraculous, impressive as hell, and impossible. Let's talk about Dante's Inferno. It's a poem. In Italian, it rhymes. When you translate it, do you translate it literally word for word so that you get the exact plot and images and individual words Dante chose? Or do you translate it so that it rhymes at the sacrifice, sometimes, of much of the above? Before you answer, consider that much of Italian rhymes, much more than English does. So rhyming poetry sounds different and means differently to Italian ears than it does to English speaking ones. This kills me. "Um, I found a head. Does anyone know whose head this is?" "It's yours you idiot." "Really? Bummer. Man, I have a great body though, huh? Without my head, I look years younger. Anyone want it? Free head?" Another example is this: when Sam meets Meredith in Goodbye For Now, she says her friends call her Max, and he says, "Not Merde?" This is a joke. Because "merde" means "shit" in French. He calls her Merde throughout the rest of the novel because, to English-primary ears, Merde sounds like a cute term of endearment rather than a profanity meaning excrement. But what to do when you translate the book into French? My husband and I fantasized that they might change Meredith's name to Shitella or Poopina throughout in order to preserve the joke and its meaning/feeling/essence. (Right? Her name is Poopina, and the first time they meet he calls her Poop? Cute name if it doesn't mean, you know, "poop" to your ears. These are the things that amuse in my household). But instead, the very tasteful and talented French translator added a footnote the first time Sam calls her Merde which notes that it's in French in the original and otherwise has Sam call her Meredith. Which is perfect. Translation: The author is gross. I, the translator, am not gross. It is her. Not me. Cursing is a translation problem even in one's own language. I'm a curser. I curse. I curse at home. I curse in print. To my ears, it does not sound crude or dirty or especially edgy. I grew up with cursing. My father was a curser before me. He was a precurser. (You see how complicated language is?) I curse because I really can't see denying myself any of the language available to me. I want it all. But if you're offended by cursing, it sounds different to you, it means something different to you, than it does to me. Simply, you need a translation, just like someone who doesn't read English. What I mean by -- and not just literal meaning but everything that goes with it: sense, feeling, emotion, reference, character development, setting, local color -- "damn" or "shit" or whatever is simply not what you hear when you read those words. It's a disconnect. It's a translation problem. I don't intend to indicate that this character is crude or course or morally bankrupt or religiously doomed because to me cursing=normal. And in fact, in deference to those who would be offended, there's not a lot of cursing in my books. There's not a lot to begin with, and then I take a lot of it out in editing. Each time I come across a "bad word" (as if words could be bad), I consider whether someone out there might be offended and whether or not I could successfully change it to "crap" or some such. My first editor actually asked me to increase the cursing because she thought these were characters who would say "shit" rather than "crap." She was right. Ironically, I hate yelling. All yelling. I hate being yelled at. I hate being yelled near. I can't abide people who yell at one another, at their kids, even at tv screens. When people yell near me, I leave. Or cry. Or both. Cursing is not about anger. And I certainly never ever ever say it to or at anyone. The French translation of Goodbye For Now is also special because it's the only one I understand even a little bit. I don't read any of the other 25-plus languages into which it's been translated. But I read a little French. I understand the very lovely French edition mostly because I know what it says. But it's also a wonder to read my own words unfamiliarly, to make new to me something I not only made up but have read dozens of times. It's as close as I come to the experience of being a real reader of my own book. Kind of cool.

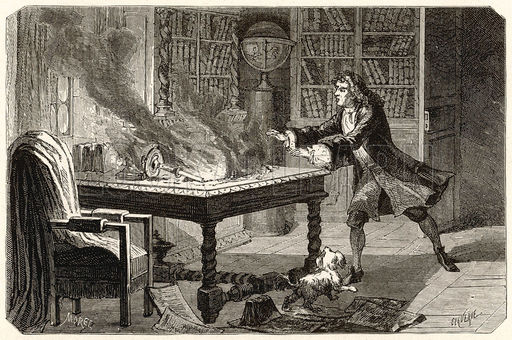

Here is an article from Slate last week on the first book ever to be written on a word processor. In 1968. The book's author, Len Deighton, explains, "Having been trained as an illustrator I saw no reason to work from start to finish. I reasoned that a painting is not started in the top left hand corner and finished in the bottom right corner: why should a book be put together in a straight line?" Which is a good argument. I'm not sure I'd have had the bravery/foresight/cash involved in knocking out a window of my home in order for a crane to install a 200-pound, $10,000 (1968 dollars, at that) typewriter in my home office, but the idea of processing words strikes me as remarkable even if you'd never heard of it before. IBM evidently never considered that these machines would be used by individuals. I get that these things were huge and expensive, but processing words has always, always struck me as the ultimate killer app. It's not that I can't imagine writing a book longhand or on a typewriter -- I can, and I imagine it was torture. As both a reader and a writer I came of age in a time of flexible, malleable, negotiable text. Messing with text feels like my birthright. It's as hard for me to imagine writing novels without a computer as it was for IBM to imagine me writing them with one, but I'm pretty sure I'd have chosen a different career. I thought a lot a lot a lot a lot about writing and technology for and of and as Goodbye For Now. Technotext is my text. But processing words, well that's just something I take for granted. I also like the note about how afraid he was of losing work to power outages. I am an anal backer-upper, so I totally get it, but anything electronic seems less worrisome than the alternative. I have long wondered how writers ever used to leave home in the days of hardcopy. What if your house caught on fire? Or the roof fell in? I have always had this backup plan: I would leave my hardcopy in the refrigerator. I mean dropbox is pretty awesome, but as a fallback, I'm not really doing anything with the meat drawer anyway. "Why oh why must I live in a time before cloud storage? Perhaps I am being karmically punished for caring more about my desk than my cute little dog."

We are moving. Just across town. Less than five miles away. A minor change as far as these things go. But oh, as you know, moving is hell. This is because first you have to cull all your stuff, which is hard. Then you have to pack it, which is hard. Then you have to move it, which is hard. Then you have to unpack it, which is hard. Not to mention the business of procuring a new home and finding someone else to love the one you're in. Not to mention the emotional upheaval involved in the leaving of something as monumental as a home and the adoption of something as monumental as, well, another home. Roughly .0007598% of the boxes of books. Too. Many. Books. As you also know, when you move, you turn up a whole bunch of crap that needs to be thrown away (that is, recycled, donated, sold, or thrown away). One of the things I turned up today was the first printed-out drafts of each of my books. The best word for these is "fumblings." They are trying things. They are seeing what happens. They are totally free because there is so much change ahead of them. They are totally lost because they have no idea where they're going. But I do. They are harbingers, but they weren't at the time. They're amazing to look at because they are, indisputably, where you've been, but you just can't imagine how they got where they went from that place where they were. Instead of buying boxes and/or begging them from liquor stores as in days of yore, KarmaBoxx delivered these big, strong, clean plastic bins to my door and will pick them up from me after I move. Cheaper, easier, more pleasant, and much greener than cardboard boxes. Cool, no? At the moment, from the bottom of the box-canyon, it doesn't feel like it, but moving houses is not nearly so dramatic, so changeful, as writing novels. My new house will have all the same words as my current one, the same general plot as well. That's true of the barest percentage of first drafts of my novels. And meanwhile, back at the beginning of book writing again, as I fumble about with the start of #3, nothing is so comforting as those early lost drafts. See where they were? See where they went? Doesn't seem possible, but evidently, it is. My extremely cute and beloved current home. I'll post a pic of the new one next week when we're actually in it. Meantime, if you're interested in buying a very lovely house in the CD in Seattle, please do be in touch.

Retreat is a word that always makes me giggle because, in my line of work, it means going off to the woods/sea/countryside for writing/reading/contemplation/quiet reflection/time to one's self/a room of one's own whereas I am always instead thinking of running away from marauding hordes. English is a funny language. I spent last week at the first kind of retreat -- the kind in the woods with writing, reading, reflecting, and time and room of my own. It was my very first retreat of the non-running-away kind, and it was pretty of amazing.Hedgebrook is a retreat for women writers on Whidbey Island, WA. One can apply for residency and stay for between a couple of weeks and a couple of months. One can pay to attend workshops and salons. Or one can come teach, as I did. I'd have done so with joy and delight just for the pleasure of doing it and of working with and meeting such talented, committed writers, but when payment turns out to be a cabin to myself for four days with all meals gloriously prepared (and delicious)...I actually lack words to sufficiently describe this experience. The best one I have is generous. It was also a week left to the imagination. There's no phone. Cell reception was essentially non-existent. No wifi in the cabins. So alone felt really alone, disconnected, isolated. Good for the imagination certainly, but good for the imagination is not itself always good for the soul. Hedgebrook is a safety-first sort of place. They warned me that the fire alarm in the cabin rings the fire department directly, so don't burn toast. There's a fire extinguisher, a total ban on candles, a battery-powered lantern, a panic button for instant police signaling, and air horns on both floors. But the provided flashlight is one of those small emergency crank things that sheds a tiny amount of light on only the half square foot immediately in front of you. The way back from dinner is woodsy, windy, and wet, branches blowing, rain spattering, noises noising...let's just say it was a long quarter-mile every night. It is perfectly, perfectly safe, but I imagine things for a living...and imagine I did. My friend Tara, of the lovely blog Tea and Cookies, points out that being in a city is much more dangerous than being in the woods on a rural island. True enough. She says there is much more to fear from people than animals. But I was not worried about being attacked by a bear. I was worried about being attacked by a zombie. Freaking Joss Whedon. I get it. I do. Really. But one wants to see a film and then move on with one's life whereas the memory of Cabin in the Woods prevented me from achieving the proper zen retreat state. I thought too much about the other kind of retreating -- the kind where you have to run away from a redneck zombie torture family who might be lurking just outside the beam (a charitable term in this case) of your so-called flashlight waiting to cut you open with a rusty saw. Thankfully, this did not harsh on my productivity -- only on my mellow and my willingness to leave my cabin for really any reason at all. Except food. Oh the food. There are times in one's life where someone else cooking is like the greatest thing you can imagine -- besides zombie survival -- and I am at one of those times apparently. Meantime, novel #3=underway. Not very underway. But underway nonetheless.

Here's something that's awesome: when random people you don't know write to you out of the blue to tell you they love a book you wrote. Twenty years ago if you read a book and wanted to tell the author so, I guess you went to the library, did some research (microfilm/fiche of articles written about that author that might mention a hometown by way of local color?), figured out where he/she probably lived, located a white pages from said hometown, and crossed your fingers the address wasn't unlisted. And hand wrote a letter. I have a borderline unhealthy amount of author-worship myself and did even as a child, and it's not just that I never did this; it never even occurred to me to do so. Nor anyone I know. My sister and her friend Sharon used to write love letters to Kirk Cameron pledging marriage. But no one I knew ever wrote to an author pledging so much as admiration. Now the research involved in locating an author is a .19 second google search. If you read your books as e-books, sometimes the link is actually embedded, so it doesn't even take that long (what will you do with your extra .19 seconds?). So lots and lots of people take a moment after finishing a book to look up the author. In fact, I wonder if it's most. And lots of those people take a few minutes or a little more to write an email or post on my FB wall or send me a tweet as to how much they like the book. This is, of course, gratifying in the extreme, and I am always very grateful. I knew I'd get some of those emails from my experience with book #1. What I didn't count on this time was how sad some of the letters would be, how downright heartbreaking. The book is about mourning, and a lot of people have written to me about their own losses, and those are very sad. Topically, I've gotten some emails from tech folks too and some from doctors, but the best/worst are the heartbreaking ones. I worked very, very, very hard to consider thoroughly and represent carefully mourning and loss from a variety of perspectives. In fact, though I didn't (and still don't really) know who these note-writers are, I thought of them while I was writing. I kept in mind always parents who lost kids to leukemia and brothers who lost brothers in car accidents and wives who lost husbands too early and what a shit cancer is. So I am grateful that this book gives some comfort/solace/recognition/support/diversion/remembrance to people who see themselves in it. But I am very, very sorry too. Meantime, if you've read the book and taken some time to write me a personal note about it, thank you. It means the world. P.S. That's not really my sister up there. Here's my actual sister (with my actual nephew). Kirk should be so lucky. P.P.S. Do you look up authors upon finishing their books? Do you usually drop them a note some way or other if you liked it? Do you ever write to authors of books you hate to tell them so?

It is, more or less, my one year anniversary of not teaching. Since last June, I've been out of the classroom, out of academia. Since last June, when someone asks me what I do for a living, the answer has been "novelist" rather than "English professor" as it had been for the ten previous years. This past September was the first September I didn't go back to school since I was three. Literally.

Die-hard -- I often call them "real" -- academics get time off to write. I left graduate school right before I'd have gotten a year of stipend in exchange just for writing without having to teach. I left my first teaching job before I had enough years accumulated to apply for a sabbatical. I wasn't tenure-line at my second so never even had the opportunity to apply. So while this year was my first opportunity to write without also being in the classroom, in fact it's not that unusual for people in my profession(s). But for me, it's been life changing. One thing is child+book writing+full-time teaching position was too damn much. Getting rid of one of those makes doing the other two one-hundred-percent more sane. Another thing is what happens when you elevate your hobby to your career and put all of that time and energy and creativity and intellectual effort and resources and priority into something you used to just make time for and squeeze in as you could. The difference shouldn't have been nearly as surprising as it was. Teaching full-time, reading and lesson planning, grading all those papers, e-mailing with all those students, commuting, working with colleagues, dealing with all the crap that comes with any job...putting all that time and energy into writing instead makes for a lot of time and energy put into writing. Basically, I wrote the whole of Goodbye For Now between June and September. People think that's mind-blowingly fast, and it is (and was only possible because I'd worked on it the previous summer and had it all planned out and ready to go in my head), but also, put 40 or 50 hours a week and all your creative energies into something, and you're bound to see some pretty steady progress. I miss teaching -- the classroom part, the good days. I do not miss grading at all. I thought it would be hard to write without talking about and teaching about writing, but it wasn't. I thought it would be hard to write without a deadline -- September and the start of classes -- on the other end, but it wasn't. I thought it would be hard to write at home by myself inside my head all day instead of interacting with students and colleagues and a whole out loud world out there, but it wasn't. I worked so long and so hard and so formatively at teaching I thought giving it up would be much harder and stranger than in fact it's been. It feels like it's been much, much longer than a year. One of the first things I learned in graduate school for literature (this was in the late 90s) was this: the author is dead. One of the first things I learned about being a published novelist was this: the author is, frankly, more important than the text. The author is what's valuable, marketable, and for sale. What the author thinks -- about everything -- is everything. These are opposites. So I ask you: is this one of those cases where the academic literary theory and the actual literary life do not match up, or is the author new born or resurrected or somehow undead? Because of my the-author-is-dead indoctrination, and for quite a few other reasons, the commitment to social media is new for me, and its effect at the moment is this: First I have an idea. Next I have a decision to make. Is that idea very pithy (a tweet), slightly less pithy but still bite-sized (a Facebook post), full and wider reaching but kind of random (a blog post), full and wider reaching but connected and content driven (my website), or simply giant (you know, a book). That last one, of course, is kind of the point. I've always thought interviews with actors is something of a strange thing to make up such a large percentage of talk shows and late night tv. These are people who get paid to say things other people think and write, to become people who they aren't. The better they are at doing so, the more successful they are at the profession for which they are so lauded. So asking them about themselves, who they are, and what they think seems like it's kind of missing the point. Here too. Good novelists are good at the long form -- slowly developing characters and long narrative arcs and careful descriptions and fully explored themes and ideas. So pretty much the opposite of the tweet. It's not that twitter isn't fun; it just seems like I'm not the right person to do it. Not so, of course, and for the same reason. Actors are interesting, pretty, dynamic people who perform well in all kinds of ways (i.e. they also make good talk show guests) and who learn much that's useful to us all from embodying so many different characters. And good writers are good writers with smart, interesting things to say...across a variety of mediums. I've been thinking too that fifteen years ago when I was in grad school, the output of writers was pretty much limited to their writing. Dead was kind of the only available option. Enjoy a book? Want to read other things that author has written? From the dawn of recorded text up until about a decade ago, you could go buy another book by that author. You might have been able to hunt down an article by or about as well by watching your newspaper/magazines when the book released and/or by going to the library and doing a little research. This was true too if you just wanted to know more about the author or book -- if you missed the reviews that ran on release, you were pretty much SOL. Maybe the author was only ever dead because there wasn't another option. As soon as there was, authors made a stunning realization: not dead yet. And, you know, it's nice to be in touch with readers. It's nice to have thoughts that go nowhere much. It's nice to write in a way that feels ephemeral (even though it's not), to write small things in small ways. It's nice that when I read about a book, I can find out more about it and its author basically instantly.

All that said, does reading everything else an author produces (his/her blog and FB page and twitter feed and random articles here and there) take time away from my reading other things I'd enjoy more? Almost certainly. And does knowing more about an author enhance my enjoyment of a book? I'm not sure it does actually. So I ask you...Authors: dead or alive? Not which they are, but what's your preference? Today I read this remarkable Guardian article about Toni Morrison with whom I fell in love in college. She's incredible, and the article says a great many interesting things, but the one that stopped me was this: "It is hard to believe Morrison is 81. She started late, her first novel, The Bluest Eye, written when she was 39 and a senior editor at Random House."

First off, 39 is late? Really? Maybe it's not early but late? The New Yorker's up and comers list is "40 Under 40," and that seems about right to me. Writers under 40 count as young, early, up and coming, ahead. This is not to say that writers over 40 are old or late or behind -- not at all, in fact -- but calling 39 late seems strange to me. I imagine what this writer really means is that Morrison is so talented and so decorated (i.e. she's a Nobel Laureate in addition to quite a few other remarkable honors), and we somehow expect that kind of talent to be inherent, built-in, inborn rather than earned or developed. This brings me to what strikes me as the second remarkable, thrown-away point in those couple sentences: she was a senior editor at Random House at the time. No matter how inherently talented you are, writing good books (or, hell, bad books) takes time. Lots of it. So does being a senior editor at Random House. So does rising to be a senior editor at Random House. This is also part of why 39 seems young. Morrison went to college, then graduate school, then taught at a couple of colleges for a few years, then was a textbook editor before becoming a senior fiction editor and finishing her book. That's not late -- that's pretty much right away. She can eat off writing novels now, sure, but no one starts off that way. Third is that innocent little "and." "...her first novel, The Bluest Eye, written when she was 39 and a senior editor at Random House." Lots of us -- most of us probably -- write our first novels with an "and." We have a job and we write. Lots of us also have kids. Morrison had two and was raising them solo and was a senior editor at Random House and was writing her first novel. Later in the article, it says she got up at 4:00 every morning to write. It strikes me that she could reasonably have gotten up at 5:00 instead or written every other morning or just on weekends, published her first book at 45 or 47 instead of 39, and still been ahead of the game. And then there's this bit: "It is hard to believe Morrison is 81." It's not clear if that's because she seems younger or because it seems like she was so recently 39 and publishing her first book or because it seems strange in our culture to be publishing novels -- as Morrison is this summer -- at the age of 81, but I gather it's the latter. There's much in the article about her always napping after lunch, never having to feel guilty about anything anymore at 81, forgetting where her keys are and what they're for, having a clear picture of the past just not the present. It's interesting this impression that writing is for young people -- 39 is late to start, 81 is old to publish -- when it seems in so many ways like it'd be the opposite. Is it cultural? Other cultures value the wisdom and experience of their elders more than we do? It also seems to me to tie into all of the above: when your children are raised, when you don't have to work full-time at a non-writing job to support your writing, when your head isn't full of parenting and working, when you aren't so sleepless and exhausted, when you've had some education and life experiences and perspective, when your past is clearer than your present, when your past is presenter than your present...that seems to me like exactly the time to be writing novels. |

About The AuthorLaurie Frankel writes novels (reads novels, teaches other people to write novels, raises a small person who reads and would like someday to write novels) in Seattle, Washington where she lives on a nearly vertical hill from which she can watch three different bridges while she's staring out her windows between words. She's originally from Maryland and makes good soup. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed